Democracy for Realists

No book has done more to change my thinking on democracy than Democracy for Realists by Christopher H. Achen and Larry M. Bartels. The book is an attempt to square some rather inconvenient facts about voter competence and decision making with more optimistic visions of democratic empowerment. The main goal though is to better understand how existing democracy works. I think it’s worth a deep dive into how things work now before considering how they might be improved. So the focus of this post, much like their book, is simply on describing how things seem to work now. But to be clear at the start, I am not advocating against democracy - despite the fact that this post is quite critical, I still think democracy is the best available system.

Achen and Bartels start by laying out what they view to be a popular, but unrealistic theory of democracy, which they dub the ‘folk theory’ of democracy.

The Folk Theory of Democracy

In the conventional view, democracy begins with the voters. Ordinary people have preferences about what their government should do. They choose leaders who will do those things, or enact their preferences directly in referendums…Democracy makes people the rulers, and legitimacy derives from their consent

There are two broad ways in which this rule of the people could happen

- Prospective Voting

- Retrospective Voting

Prospective voting requires voters to have preferred policies, decide which candidate is closer to those policies, and then vote for the candidate who comes closer to matching their policy preferences. This is arguably the most optimistic theory of democracy, but it requires substantial time, interest, and knowledge on the part of voters.

An alternative, and less cognitively demanding version of democracy holds that voters act retrospectively. Rather than undertaking a detailed study of future plans, voters evaluate if the incumbent party has done a good job. The most famous version of this in the U.S. is the, “are you better off than you were four years ago?” question in presidential elections. Achen and Bartels describe retrospective voting with an analogy, saying:

Ordinary citizens are allowed to drive the automobile of state simply by looking in the rearview mirror. Alas, we find this works about as well in government as it would on a highway

Evidence against Prospective Voting

I’ve organized their objections into three broad categories of my own making.

1. People don’t have stable policy preferences

The evidence against prospective voting is quite strong, and goes back at least to the 1960s and research from Phillip Converse that asked voters about policy and concluded that many citizens, “do not have meaningful beliefs, even on issues that have formed the basis for intense political controversy among elites for substantial periods of time.” (p.32) Converse found that individual policy beliefs were not strongly correlated to party issue stances and that those beliefs were not stable over time in follow-up surveys. Later reserach (e.g. Follow the Leader by Gabriel Lenz) also suggests that to the degree policy beliefs are correlated with party stances they are often the result of voters adopting the already existing policy views of their chosen party. This may sound unexpected or condescending, but I want to point out there’s no general reason that individuals should walk around with strong ideas about what to do with social security, nor should we expect them to want to spend time reading detailed budgeting documents. I am not suggesting that people are stupid, I’m suggesting they have more fun ways to spend their time than becoming policy experts.

Most people’s knowledge of politics is likely about as strong as your knowledge of a popular sport that you personally don’t watch. You might hear about it from friends who are passionate and maybe it’s on the news sometimes. You can name a handful of players. And that’s entirely fine, because you don’t need to be interested in the sport. It’s clear though that this isn’t a sufficient knowledge base for you to have carefully considered views on what the future of that sport should look like or which players deserve special recognition. Similarly, voters, as a whole, are simply not in a situation where they can effectively execute prospective policy-based voting.

2. We don’t know how to solicit and aggregate those preferences

Asking voters about their preferences turns out to be much trickier than it initially seems. People’s responses are quite sensitive to the exact question being asked, referred to by political scientists as the ‘framing’ of the question

The psychological indeterminancy of preferences revealed by these “framing effects” (Kahneman, Slovic, and Tversky 1982) and question-wording experiments calls into question the most fundamental assumption of popular democratic theory - that citizens have definite preferences to be elicited and aggregated through some well-specified process of collective choice (Bartels 2003).

Even if we were to be able to consistently get preferences from individual voters work in choice theory by Kenneth Arrow revealed that we cannot aggregate those individual opinions into something that represents public opinion.

Arrow’s theorem demonstrated with mathematical rigor that what many people seemed to want — a reliable ‘democratic’ procedure for aggregating coherent individual preferences to arrive at a coherent collective choice — was simply unattainable

3. Preferences may be for impossible outcomes

A study of the tax revolt period in the U.S., exemplified by California’s proposition 13 referendum showed the fundamental tension. Sears and Citrin (1985) record

Throughout most of the tax revolt period the electorate wanted ‘smaller government’ but also the same or increased spending on specific services…But this combination quite clearly involves a logical tension, and there were no other beliefs that we could add into that particular equation that would render that combination more sensible…none of these escape routes succeeded in explaining away this basic anamoly; it prevailed even among people believing in small amounts of waste, the most sophisticated voters, and both liberals and conservatives.

An additional example comes from a change to require referendums for some Illinois county fire fighter funding. Despite a general preference for good fire protection services and a high likelihood that the savings from lower taxes are smaller than the increased insurance expense of worse fire coverage, voters in Illinois wound up trading off 43 cents are year in lower taxes for a 7% increase in fire fighter response times.

Evidence Against Retrospective Voting

In response to the growing evidence that voters do not have a detailed list of policy preferences that they evaluate candidates against, the theory of retrospective voting began to grow, arguing that voters simply need to reward or punish incumbents at the ballot box rather than evaluate the likely impacts of complicated policy proposals from multiple candidates.

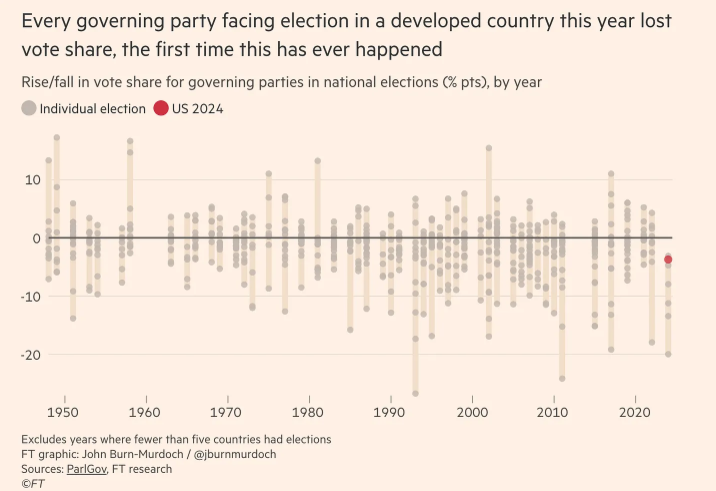

The main issue here is not that voters do not react to conditions over the time incumbents are in office, it’s that they seem equally responsive to things that are or are not within the parties control. Achen and Bartels find that voters blame incumbents for droughts, floods, and shark attacks. There’s some (disputed) evidence that voters may also punish incumbents for recent failures by local sports team. Using a centurty of weather data, they conclude that ‘2.8 million people voted against Al Gore in 2000 because their states were either too dry or too wet’ - enough to change the results of the election.

When it comes to economic retrospection, voters myopically focus on the election year and not on the entire term. A study of the great depression and its global impacts shows that rather than leading to an ideological shift in voters it lead to anti-incumbent sentiment during the depression and pro-incumbent during the recovery. Regardless of the policies and ideologies of the governing parties.

The result of this kind of voter behavior is that election outcomes are, in an important sense, random…we do not mean to suggest that outcomes are random in the literal sense of being utterly chaotic or unpredictable…Our point is that the most important single factor in who wins - myopic retrospection - is, from the standpoint of democratic accountability, essentially arbitrary.

There is still some value to retrospective voting. A mayor who fails to provide basic government services like trash removal and clearing snow from streets in winter will likely not stay mayor, and thus we find that regardless of ideology most mayors manage to keep the basic functions of local services working.

What now?

There are, potentially, a near limitless number of things that change when we start to think about democracy in terms of groups, parties, and power rather than aggregations of individual policy preferences. But I’ll highlight only a few initial thoughts here.

Two-party democracy needs both parties committed to democracy, or eventually anti-incumbent votes will lead to democratic backsliding and potentially the end of democracy. Donald Trump won elections that we would have expected a generic Republican candidate to win. When one of the two parties ceases to support democracy and then gains power as a result of anti-incumbent voting, they can start to dismantle democractic systems. Even if unsuccessful in their first attempt (Jan 6th, 2021) the party will be returned to power (November 2024). The only way to have long-term democractic stability is for all parties involved to be committed to democracy.

The policies of electoral winners are not necessarily popular. For a current example, see survey data from Americans voted for Trump, but never supported Trumpism over at Strength in Numbers. People are not prospective policy voters, and so even when those policies are stated and have easily predictable consequences, voters may still vote for a candidate who supports policies that they themselves do not support.

Making changes requires forming broad coalitions. Voters are brought in not by detailed policy proposals, but by feeling that the political party or coalition they are joining is one that welcomes them and values them.