End Exclusionary Zoning

Affordable Housing and Municipal Zoning

It is illegal to build affordable housing in most of Louisville. While there are a lot of contributing factors to the shortage of affordable housing in the U.S., one major reason it exists is because of policies we have intentionally put in place to reduce the supply of housing out of fear of a possible decline in property values and having to share ‘our neighborhoods’ with people of different classes and races. It is illegal to redline a map and explicitly exclude people from buying in certain neighborhoods on the basis of race, but it is a legal and widespread practice to use zoning ordinances to restrict the supply of affordable housing. In practice, zoning restrictions ensure high levels of racial and economic segregation.

What is Multi-Family Housing and why is it more affordable?

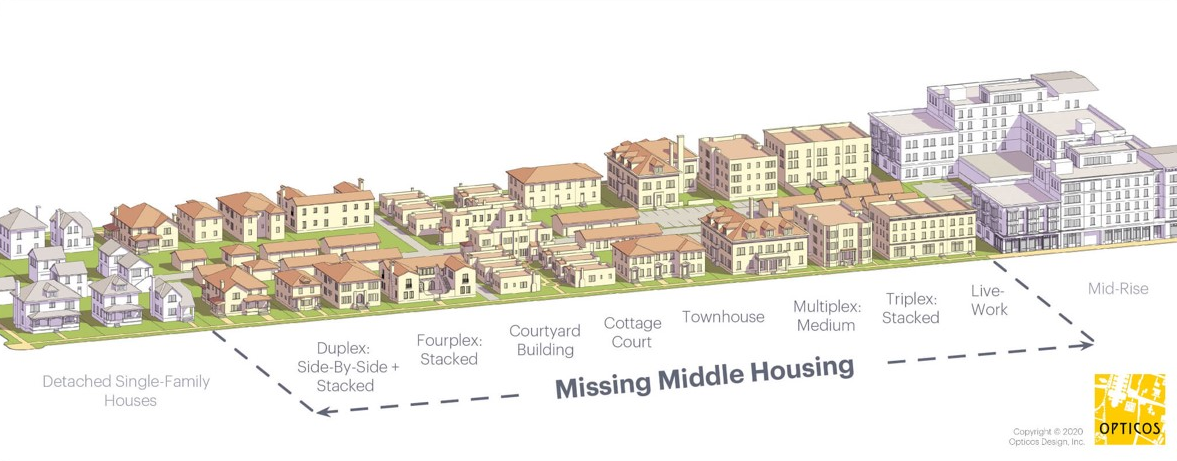

Multi-family housing includes a lot more than just large apartment complexes. There’s a wide range of types of housing that can include multiple families. A review of Louisville’s current housing situation refers to this as the ‘missing middle housing’. Louisville currently has limited areas zoned for large apartment complexes and huge swathes of land dedicate exclusively to single family housing.

Single family housing starts out less affordable because it requires more land per person, but additional zoning restrictions around minimum lot sizes and required parking spaces also drive up the cost. If you want to learn a little more about zoning and housing prices in general, this is a good 10 minute video explaining the key ways restricted zoning makes housing less affordable.

Zoning in Louisville

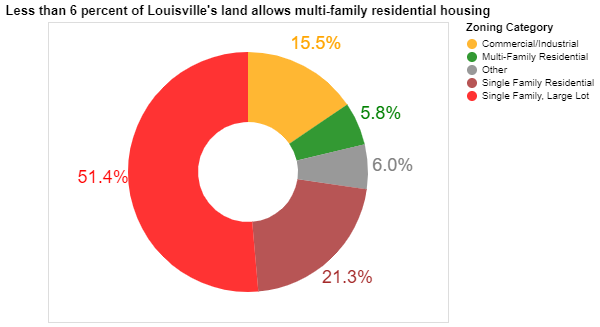

Louisville’s zoning data is available online and is regularly updated. I used the most recent data available for download (it’s a little unclear if it’s from 2020 or 2022 in the documentation, but it’s recent enough for this analysis) and divided the official zoning designations into five broad categories:

- Multi-Family residential: affordable housing is legal in these areas

- Single Family Residential: restricting housing supply by mandating single family homes

- Single Family Large Lot: highly restrictive zoning that requires a 9,000 sq. ft. lot size for single family dwellings.

- Commercial/Industrial: includes enterprise zones and anything else clearly commercial

- Other: several very small categories that are most likely related to commercial use, although this does include the ~1 percent of land that is zoned for both commercial and residential uses

An overview of zoning types is provided by Louisville Government, and there is also an official map with additional details.

Louisville is not zoned for affordable housing

- The overwhelming majority (73%) of Louisville’s land is reserved for single family dwellings.

- Only 6% of Louisville’s land allows multi-family structures to be built, even if we restrict the analysis to residential land it’s only 7% of residential land that allows multi-family dwellings. In other words, 93 percent of residential land in Louisville is reserved for more expensive single family units

- The most common single-family zoning code (R4 zoning) requires a 9,000 sq ft lot size, a requirement first adopted by the city in 1963. This type of zoning makes up a over half of Louisville’s land and makes even single family homes more expensive than they would be if they could be built on smaller lots.

Zoning Map

We can also look at where multi-family dwellings are allowed. The small green patches represent multi-family housing. Typing an address into the search bar will place a marker on the map locating that address, making it easy to find the zoning for your residence.

Ending Exclusionary Zoning

I was inspired to look at Louisville’s zoning regulations after reading Matthew Desmond’s new book Poverty, By America. It’s a fantastic book, and one thing he emphasizes throughout is the many different ways in which we construct barriers that are intended to keep the poor in poverty. Modern zoning acts as a wall to keep people out.

You can learn a lot about a town from its walls. Our first walls were primitive things: sharpened tree trunks, mud and stone. We learned to dig trenches and build parapets. Someone in the American West invented barbed wire. Today, we fashion our walls out of something much more durable and dispiriting: money and laws. Zoning laws govern what kind of property can be built in a community, and because different kinds of properties generally house different kinds of people, those laws also govern who gets in and who does not. Like all walls, they determine so much; and like all walls, they are boring. There may be no phrase more soulless in the English language than “municipal zoning ordinance.” Yet there is perhaps no better way to grasp the soul of a community than this. (p. 113 - 114)

There is good social science research on the incredibly beneficial effect of moving to lower-poverty neighborhoods - even if the income of the individual moving is not changed. These moves are beneficial for adults, and they are especially beneficial for children. As Desmond points out, it almost feels silly to need to cite research to show that the environment children are in matters to them. Of course it does - that’s why those of us who have children and are lucky enough to have choices spend so much time and money on shaping our children’s environment, their schools and their neighborhood.

Deconcentrating poverty and ending neighborhood segregation is one of the first things we must do to reverse the impact of decades of intentional policies promoting segregation by race and income. Desmond writes:

How can we, at last, end our embrace of segregation? The most important thing we can do is to replace exclusionary zoning policies with inclusionary ordinances, tearing down our walls and using the rubble to build bridges. There are two parts to this. The first is to get rid of all the devious legal minutiae we’ve developed to keep low-income families out of high-opportunity neighborhoods, rules that make it illegal to build multifamily apartment complexes or smaller, more affordable homes. We cannot in good faith claim that our communities are antiracist or antipoverty if they continue to uphold exclusionary zoning - our politer, quieter means of promoting segregation. (p. 165-166)

There is already at least one example of this in the United States. New Jersey’s supreme court prohibited exclusionary zoning and required municipalities to provide their ‘fair share’ or affordable housing. As a result, they’ve seen a huge increase in affordable multi-family units being built across the state (Desmond, p. 169)

It’s long past time to tell our elected officials that we want to change our zoning codes and build more affordable housing. We should join in saying:

This Community’s long-standing tradition of segregation stops with me. I refuse to deny other children opportunities my children enjoy by living here. Build it. (p. 170)

How to Get Involved

Louisville is currently having meetings about zoning reform. Unfortunately, these meetings tend to be dominated by current homeowners who tend to oppose changes that would increase affordability. It’s important that people who want to end exclusionary zoning make their voices heard either at the meetings or through phone calls to elected representatives.

Recommended Resources

Local Organizations

- Coalition for the Homeless

- Metropolitan Housing Coalition

- Look up Contact Info for your Metro Council Member

- Land Development Code Reform: This is a current effort to reform Louisville’s zoning codes

Local Analysis

- Code for this analysis

- Confronting Racism in City Planning and Zoning by Louisville Metro Planning and Design Services

- State of Metropolitan Housing Report, 2022 by The Metropolitan Housing Coalition

Books about Race, Poverty, and Housing in the United States

- The Sum of Us by Heather McGhee

- Poverty, By America by Matthew Desmond

- The Color of Law by Richard Rothstein